Emails are terrible identifiers

For a long time now, email addresses have been the predominant identifier deployed for user accounts on the web. Almost any service that you sign up for will require you to sign up using your email address and, at some point, prove you have control of that email address by verifying some secret that they email you (or via OAuth). This is an anti-pattern, but one that was necessary because the internet and the world wide web were built without an identity and authentication layer prescribed via RFC or standard. Implementers were left to their own devices and did the best they could with the tools that were available to them.

This is one of the core issues that Decentralized Identifiers (otherwise known as DIDs) attempt to address, and it’s a subtle one that often doesn’t get very well explained in the foundational literature of Self-Sovereign Identity.

Why are email addresses poor identifiers?

Email addresses are identifiers within the SMTP protocol. They are now quite ubiquitous with a very familiar [email protected] format where the segment preceding the @ symbol is the username and the segment following the @ symbol is the host or domain where the user resides. Unsurprisingly, given the name “email,” it was designed primarily as a messaging protocol and these addresses mapped to “mailboxes.”

The SMTP protocol makes no prescriptions for verifying the authenticity of a sender, how to authenticate a user when they’re logging in to check their email, or any other authentication mechanisms whatsoever. It is purely a messaging protocol and transport specification. But they are identifiers of some kind and provide the developers of web services with something relatively unique that they can tie to a user and establish accounts. The conflation of the original intended purpose of email addresses as message routing identifiers with authentication identifiers is where the problem arises.

One problem is that email addresses are more ephemeral than we’d like to think. There are countless stories of people who lose access to their email address either because they were banned from one of the major providers (e.g. Google, Yahoo), or they graduated from university and any accounts tied to their university-provided address are no longer accessible, or they simply forgot their password and don’t have a way to recover it. Even owning your own domain and maintaining your own email address can’t fully solve this problem. There are plenty of stories of domains getting sniped when they expire, or people maliciously buying domains of defunct companies to get access to their accounts. And when that happens your whole online persona goes with it.

Several problems arise specifically from the conflation of the communication channel with the authentication channel. Because authentication mechanisms via email identifier are largely undefined by any spec, implementers are left to figure things out on their own. This has led to a number of mechanisms with varying issues. Passwords are still pervasive in 2025 despite the recent introduction of passkeys. Passwords have a number of well documented issues.

“Magic link” is a particularly popular mechanism for logging people in via email. The flow is relatively simple. You prove your ownership of an email address by receiving a link that only you and the service you’re logging into should have. You click the link, and it re-routes you to the service that you’re logging into.

One issue is primarily a UX one: the deliverability of the authentication email requires the user to be online and for all of the email plumbing to work flawlessly. Email deliverability is a dark art similar to SEO thanks to Google’s blackbox spam filtering, so unless you’re already on a high-authority domain that Google allows fast delivery for, or you pay a provider that has such infrastructure in place, you may be out-of-luck as an independent provider.

Phishing is another issue. One of the only reasons that phishing is even a viable attack is because of the conflation between authentication and communication. When a “reset password” email or magic link hits your inbox, you’re receiving both a communication and a request to authenticate. This dual-channel is exactly the vulnerability that phishing exploits.

Are there any alternatives?

To reiterate the problems we are trying to address, we need an identifier that:

- Is globally unique

- Is distinct from a communication identifier

- Is decoupled from its authentication mechanism

- Is fully in the control of the owner of the identifier

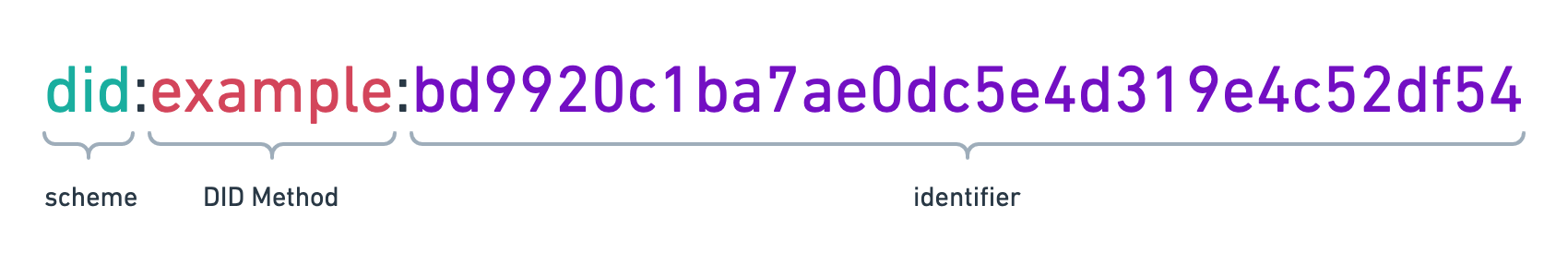

One solution that checks all of those boxes is Decentralized Identifiers or DIDs. You can read the spec for yourself for a complete overview, but basically they:

- Prescribe a format for a globally unique identifier string

- Resolve to a document that is controlled by the owner that contains details such as preferred authentication mechanisms

- Allow multiple implementations to be identified via “methods” that prescribe how to perform actions such as creating, resolving, updating, or deleting a DID and its document

- Is completely independent of any other purpose besides itself being an identifier

There are also multiple specs being developed for end-user flows that allow for using a DID for things such as logging into websites, or receiving and presenting verifiable data in the form of Verifiable Credentials (VCs, the subject of a future post).

There are several implementations of DID methods that employ different mechanisms for storage and resolution of DID documents. Some are very simple and do 1:1 mapping of an identity to a single cryptographic key (did:key), some rely on DNS (did:web), and some rely on some form of decentralized storage such as a blockchain (did:ethr). Each method has tradeoffs for usability and security. Obviously the DNS based methods have similar drawbacks to email domains.

While I do believe that ultimately a blockchain is one of the best approaches to guarantee resolution availability and security of writes to the DID document, the ecosystem does sometimes suffer from the usual crypto nonsense.

Where do we go from here?

I’m not even making the argument that DIDs are the ultimate solution for this problem. They haven’t been deployed widely enough or have seen enough real-world usage to make any such proclamation. Most development has been entirely theoretical at the spec level with very few live deployments. I am however making the argment that the status-quo is untenable and will continue to cause harm to end users and service providers. DIDs provide an alternative that at least try to address some of these fundamental issues and provide us with a testing ground to play with these ideas meaningfully. This was part of what we were trying to achieve at Heirloom.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: